Words used to arrive like guests; they were expected, announced, and received with care. Today they tumble in uninvited, coatless and loud, demanding attention the moment they appear. We live in a culture of reply, where speed substitutes for insight, and where the pause that once did the quiet work of refinement has been mistaken for weakness. Yet every meaningful sentence still begins in the hush before it is spoken.

The Age of Instant Certainty

Our tools make responses effortless; our habits make them thoughtless. The small screen is never far from the human pulse, and with it comes the false comfort of instant certainty. The moment we feel a tug of emotion, we externalize it. Comment threads become arenas; private doubts become public declarations; mistakes calcify into identities. It is not that opinion is new; it is that opinion arrives unripe and untested, like fruit torn from the branch.

There is a cost to this haste. When we treat speech as a reflex, we strip it of its moral dimension. Words carry obligations; they ask us to account for truth, for fairness, for the harm or healing they can deliver. To pretend otherwise is to deny that language shapes the world rather than merely describing it.

The Quiet Strength of Restraint

Restraint is not silence; it is stewardship. It is the choice to measure a thought before sending it into the air where it will acquire a life of its own. The old virtues still apply: prudence, charity, temperance. A prudent sentence leaves room for what one does not know; a charitable sentence honors the person as much as the argument; a temperate sentence refuses excess heat in favor of clean light.

Consider the writers we praise for clarity. Their work reads inevitable, as if the words could have arranged themselves. The illusion is purchased with discipline. Behind the page stands an author who was willing to wait. Restraint is not fashionable, but it is quietly radical; it confronts a world dazzled by immediacy and insists that time is part of truth.

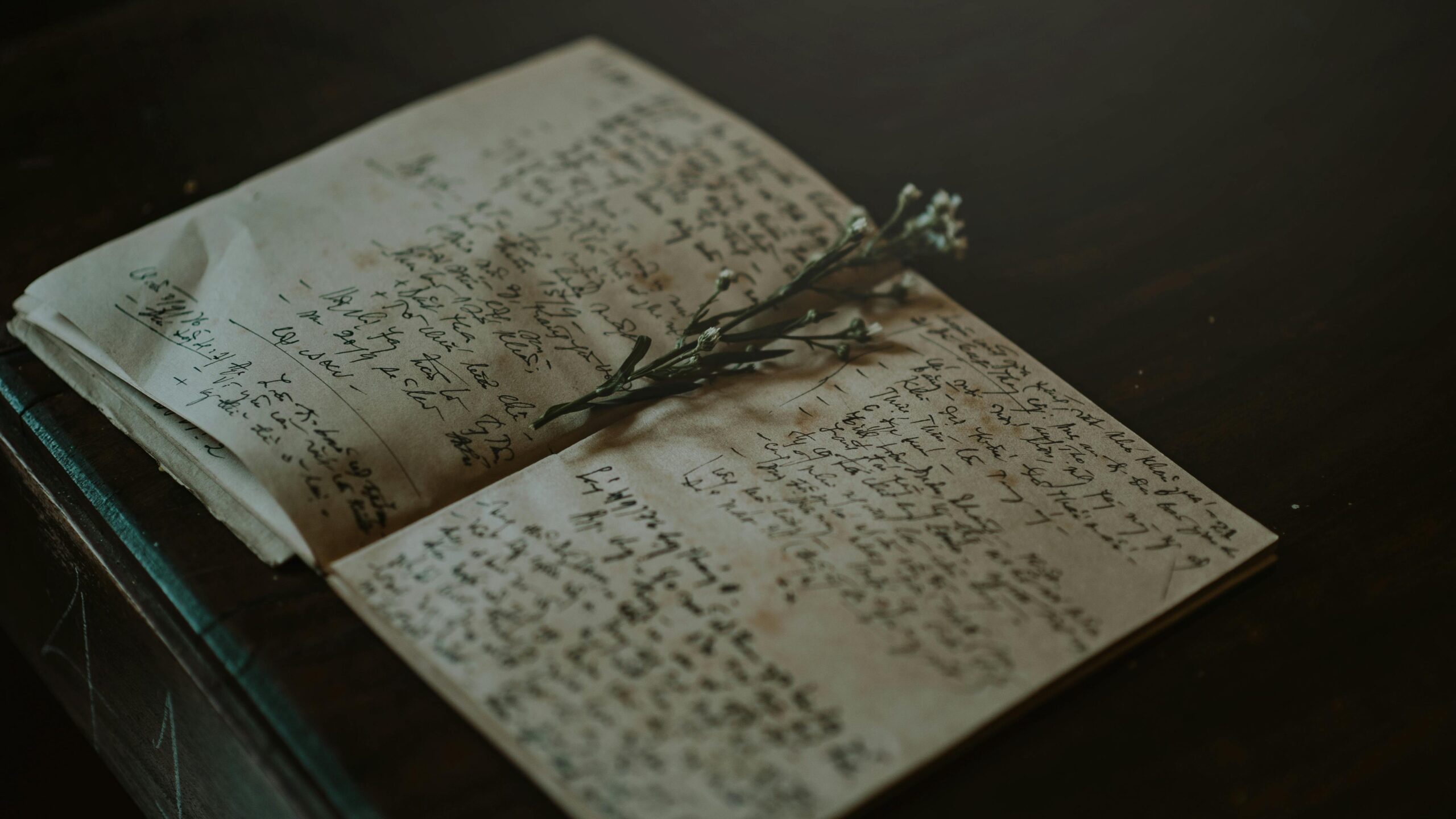

Letters, Drafts, and the Lost Delay

There was a season when the delay between thought and delivery served as a tutor. A letter crossed a river, then a continent, and the writer had a day to regret, revise, or reaffirm. Newspapers printed replies a week later; debates unfolded like measured dances rather than brawls. Even the typewriter added friction; each mistake carried the sting of correction fluid or the necessity of a fresh page.

I do not pine for inconvenience; I simply recognize the wisdom that lived inside it. Delay gave us the chance to discover a better sentence, sometimes a better self. When we reintroduce a small delay into our speaking and posting, we restore that old tutor to the room.

The Writer’s Task in a Noisy Century

If the age prizes reaction, the writer must prize reflection. Our calling is not to be the cleverest voice in the room but the clearest. Clarity is born of patience: read twice, speak once; test the claim against a second source; ask whether the barb is necessary or merely satisfying. The novelist learns this by painful repetition; a paragraph that thrills at midnight may curdle by morning. Revision is humility made visible.

In Keokuk, when the river settles into its autumn hush, the banks teach a kind of grammar. The water moves; the surface appears still. The lesson is simple: motion without turbulence can carry a great distance. A thoughtful sentence behaves the same way; it travels further because it does not splash.

How to Practice the Pause

We do not recover lost arts by nostalgia; we recover them by habit. A few small practices can restore thought to speech:

Ask a triad of questions before replying: Is it true; is it fair; is it needed? If any answer hesitates, let the draft rest.

Use the one-breath rule: If the sentence cannot be spoken in a single calm breath, the thought is not yet formed.

Prefer specifics to slogans: A concrete example forces honesty; it refuses the lazy comfort of abstractions.

Keep a scratchpad, not a send button: Draft your heat, then cool it. Many sentences exist only to be written and discarded; that is their highest service.

Honor the person before the point: If winning requires belittling, the victory will corrode the voice that claimed it.

These are not laws; they are rails along a difficult road. They preserve the dignity of both speaker and listener.

Consequences, Then and Now

We are not only individuals speaking into the void. We speak from within families, neighborhoods, churches, shops, and small towns with long memories. In places like ours, words return. The insult you hurl today meets you again in the produce aisle; the contempt you display online narrows your real world until the only friends who remain are mirrors. Communities survive on patience because they must; they know that tomorrow requires people to see one another again.

There is a broader consequence, too. In a republic, speech is the blood that keeps the civic body alive. When that blood runs hot with constant fever, reason fails. Responsible speech can cool the temperature without deadening the heart. It does not demand cowardice; it demands courage of a different kind, the courage to slow down when everything around you accelerates.

Mercy for the Tongue

Much harm has been done in the name of certainty, yet certainty itself is not the enemy. The trouble begins when certainty refuses to learn. The most convincing voices are those that hold convictions firmly in one hand and humility firmly in the other. When we think before we speak, we leave room for mercy: mercy for the person we might otherwise wound, and mercy for our future self who must live with what we have said.

The practice is simple to name and difficult to keep. It is easier to strike than to steady; easier to flaunt than to listen. But a culture that prizes steadiness outlives one that prizes spectacle.

The older I get, the more I admire sentences that arrive as if they have walked through weather. They bear marks of having faced scrutiny; they are not brittle with defensiveness, nor swollen with pride. They are strong and humane. These are the sentences that change minds and knit back what was pulled apart. They require a pause, and the pause requires us.

So let us attempt a small rebellion. Before the next post, the next reply, the next heated aside, we will breathe, we will test the words, we will search for the truer phrase. Not because we fear consequences, though those are real; not because we wish to impress, though style has its place; but because language is a gift entrusted to grown people who should know how to use it. If we recover the pause, we may yet recover the art, and with it the possibility that our words could once again carry light rather than sparks.